THE GREEN DEAL INDUSTRIAL PLAN

19 April 2023

Overall, the regulations in the Green Deal Industrial plan contain meaningful actions to increase European strategic autonomy, and make the EU more attractive and competitive for investment. The battery ecosystem likely stands to benefit from streamlined permitting for strategic projects, regulatory sandboxes for innovative technologies, and a focus on skills development.

BACKGROUND

The European Union’s energy sector has gone through significant changes over the last few years, with the rush towards climate neutrality leading to many of the first regulatory initiatives to overhaul the industry. More recently however, it is being challenged by a new series of regulations looking to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels, and increase strategic autonomy. The shock of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 sent reverberations across much of the world, and for Europe it was also a wakeup call for its dependency on imports for strategic resources. The weaponization of energy and vulnerability of the energy system led to an energy crisis, with soaring prices and a volatile energy market. To alleviate this and to avoid feeding the Russian economy, the EU looked to quickly reduce its consumption of Russian fossil fuels, with the goal to be rid of them entirely.

The first response of the EU was the REPowerEU plan, providing financial and legal measures to build new infrastructure to save energy and produce more clean energy, as well as diversify energy supplies. The plan sets the pathway to be energy independent from Russian fossil fuels before 2030, with short term measures to have an instant impact, and medium term measures to be implemented by 2027. As part of its clean energy focus, REPowerEU aims to increase renewable energy generation capacities to 1,236 GW by 2030, increasing the targets for renewables by 5% from the fit for 55 package[1]. This includes a frontloaded boost for solar photovoltaic energy to quickly increase capacities to nearly double.

In August 2022 the United States adopted the Inflation Reduction Act, seeking to improve US economic competitiveness, innovation and industry. The largest part of this is invested in clean energy, with $370 billion of tax incentives, grants and loan guarantees. These make the US a very attractive option for new investments, and now planned investments of gigafactories are under threat of leaving to the US. As explained in a European Battery Alliance discussion paper , the IRA not only stimulates the production and deployment of zero emission vehicles, it also directs investment further upstream to the rest of the supply chain with targets for raw materials and battery components made in North America. The incentives now provided in the US plus the already significantly cheaper prices of battery production in China hinders new investments into the European battery value chain, due to a significant loss of cost-competitiveness.

As Europe’s battery industry is all too aware, it is not only fossil fuel that Europe depends on foreign imports. Europe has precious little of its own critical raw materials (CRMs) that are crucial for the production of batteries, among many other industrial applications. These are needed for the transition towards climate neutrality and in the short term, to reduce dependency on fossil fuels. For this reason the EU introduced the Green Deal Industrial Plan in February 2023.

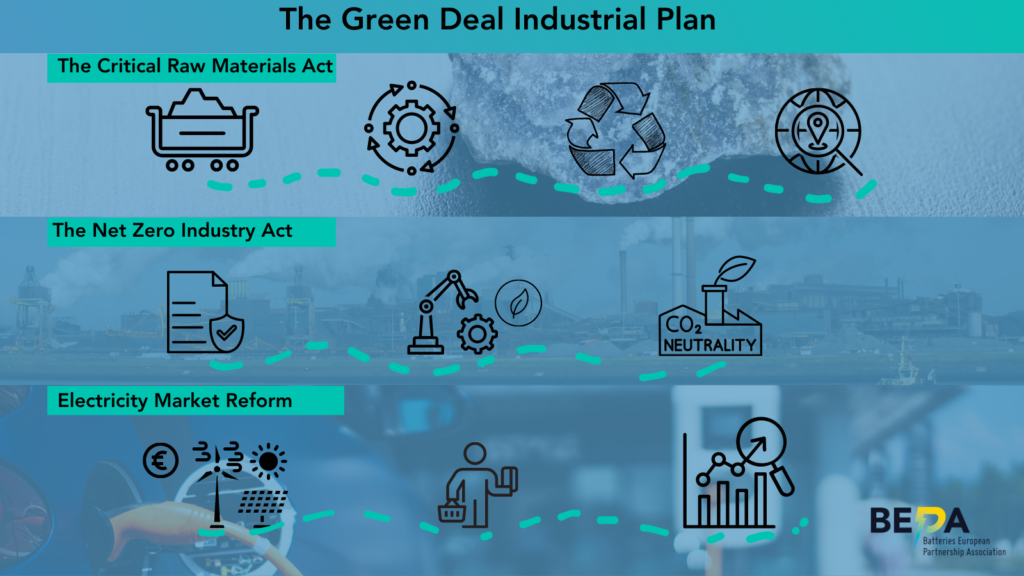

This also included three key regulatory proposals, the Critical Raw Materials Act, the Net-Zero Industry Act and the reform of the electricity market design. These initiatives aim to reduce dependency on imports for CRMs, fast-track the deployment of industrial technologies key to meeting climate neutrality goals, and to enable consumers to benefit from increased use and lower costs of renewable energy, respectively. The three regulations must now be discussed and agreed upon by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union before it will enter into force, so some amendments are likely on many of the finer details.

The trio of regulations under the Green Deal Industrial plan cover the full battery value chain, with the Critical Raw Materials Act covering beginning and end of life, the Net Zero Industry Act covering production and manufacturing, and the Electricity Market Reform addressing the regulatory and market aspect for stationary storage applications.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR THE BATTERY INDUSTRY

While the European battery ecosystem is growing, it still does not have the production capacity to meet the rising demand or achieve its targets. The greatest gaps in capacity are from raw material refining, and for cathode and anode production, which relies very heavily on imports. The ECRMA and NZIA aim to address these gaps as well as address the risk of planned investments not materializing, due to better incentives provided elsewhere, notably after the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States.

The Critical Raw Materials Act aims to provide support for the extraction and processing of CRMs in Europe, which can be an opportunity for the battery raw material sector. The fast tracking of lengthy and costly permitting processes and barriers can encourage more investment in exploiting the raw materials available in Europe. Sustainability and circularity are just as much of a focus however, with emphasis given to recycling and reuse technologies. The regulation could help grow the market and technological maturity of battery recycling, as well as second life use, in order to maximize the value and use of existing raw materials and reduce the need for new materials. This could be good news for ongoing BATT4EU projects covering end of life use of battery materials, which can likely stand to benefit from these measures upon completion and eventual entrance to market. It should be noted that these benefits are for strategic projects, therefore implementation and selection of these projects is up to each member state.

The CRM act and the NZIA go hand in hand to cover the value chain and contain generally similar measures. Both are aimed at streamlining permitting procedures and bypassing regulatory barriers, and both leave a lot of the implementation up to member states. This is in contrast to the IRA in the US, which is more focused on financial incentive through state aid. The focus is to increase strategic autonomy by boosting domestic production and reducing import dependence, rather than funding the outright deployment of clean energy to meet goals. In other words, it aims to raise the floor rather than the ceiling, by building up the domestic base of raw material production and manufacturing capacity. The EU’s high land and permitting costs, along with highest worldwide level of health, safety, environment and employment legislation for production[2] are addressed by NZIA and its strategic project status measures, helping to bridge the gap created by the IRA and improve investment attractiveness.

Addressing the gap in skills and education of the workforce has also been taken seriously, as considerable parts of both CRMA and NZIA cover this. This is something BEPA and the other initiatives of the European battery R&I community have consistently aimed to highlight in different sessions, like the EU Sustainable Energy Week and the Battery Innovation Days, so seeing this need acknowledged and addressed at the EU level is encouraging. Moreover, the accompanying texts of the NZIA in particular highlight the European Battery Alliance, not only as a source for much of the input and information about the battery aspects of the regulation, but also a success story of a European skills academy, which will act as the basis for the new ones to be created.

The electricity market design reform brings more opportunities for stationary storage, due to its focus on flexibility, demand response, storage and renewable energy deployment. The changes to tariff methodology incentivize system operators to procure flexibility options, information on grid flexibility needs, and the capacity mechanisms to support this growth. These measures help the business case for stationary energy storage, and incentivize the development of more flexibility units for both front of meter and behind the meter applications. The changes to contract length and targets also aim to give more investment certainty, following one of the aims of the reform to prevent short sensitivity and variance of prices. The setting of energy storage targets by the member states is also encouraging for the stationary storage market, as they can provide a regularly updated forecast of the capacity needs to be filled. It should be noted however that these targets are up to the national regulators, as well as implementation to reach them, such as reward or punishment for achieving or missing the set targets.

Overall, the regulations in the Green Deal Industrial plan contain meaningful actions to increase European strategic autonomy, and make the EU more attractive and competitive for investment. The battery ecosystem likely stands to benefit from streamlined permitting for strategic projects, regulatory sandboxes for innovative technologies, and a focus on skills development. Measures across the three regulations stretch across the value chain, and can help build up a localized base, with prospects for growth and development, and entrance to market.

However, as mentioned by CIC EnergiGUNE in their analysis of the NZIA in comparison to funding schemes like the IRA, it is still too early to know how all these tools will be deployed in each of the member countries and what the final effect will be. Industry players have already raised concerns that additional financial support to the battery industry is needed and the EBA is working on a set of emergency measures to boost European competitiveness. After the EBA ministerial meeting on March 1st 2023, Thomas Schmall, Volkswagen Group Board Member for Technology was quoted as saying:

‘’We need immediately an “IRA matching clause” in Europe including a revised Public State Aid Program. This must be accompanied by competitive prices for sustainable Energy which is crucial for the further implementation of the strategic Battery Industry in the EU. Above all, speed is most of what we need!’’.

BEPA will continue to support the competitiveness of the European battery industry and looks forward to the opportunity for its current and future projects to benefit from the regulations in the green deal industrial plan. We will further explore the issue of European competitiveness in the battery landscape and the role at a workshop for our members in the afternoon after our General Assembly, which will be organized on May 16.

[1] OECD (2023), Environmental tax (indicator). doi: 10.1787/5a287eac-en.

[2] https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/repowereu-affordable-secure-and-sustainable-energy-europe_en